Introduction

This chapter introduces the Unix family of operating systems and defines some of the basic components, such as users, the kernel, the shell, programs, processes, files, and the terminal. It also introduces the conventions and notations I use in this ebook.

Table of contents

- The Unix familiy

- Users in Unix

- Operating system components

- Processes and files

- The Unix file system

- The terminal emulator

- Names for commands and files

- Conventions

- Final word

The Unix familiy

Unix is a family of operating systems that share a number of similar characteristics, commands and features. There is also a UNIX™ trade mark (written with all capital letters), that is used to brand versions if the Unix family compliant with a technical specification known as SUS (Single UNIX Specification). This ebook is about using operating systems belonging to the Unix family, not about the UNIX™ specification.

When I talk about “Unix” in this ebook, I mean every current member of the Unix family, not only those that are registered as SUS compliant.

Unix first surfaced around 1969 at AT&T's Bell Labs in New Jersey, USA. Since then, Unix has evolved into a very rich computing environment suitable for many different tasks.

Some

Unix systems come with a modern graphical user interface (GUI) similar

to Microsoft Windows. A GUI is generally considered an easy to use

environment, where programs ready to run presents themselves on the

computer desktop and is started with the click of the mouse. However,

for serious systems work, the command line interface is usually more

effective than any GUI. There are also a number of Unix tools that,

for a variety of reasons, does not come with a graphical interface.

And there are situations when there is no GUI available, for example,

in a ssh session. This ebook is all about the command line

interface. If you are looking for a place to learn about Unix GUIs,

this isn't it.

Some

Unix systems come with a modern graphical user interface (GUI) similar

to Microsoft Windows. A GUI is generally considered an easy to use

environment, where programs ready to run presents themselves on the

computer desktop and is started with the click of the mouse. However,

for serious systems work, the command line interface is usually more

effective than any GUI. There are also a number of Unix tools that,

for a variety of reasons, does not come with a graphical interface.

And there are situations when there is no GUI available, for example,

in a ssh session. This ebook is all about the command line

interface. If you are looking for a place to learn about Unix GUIs,

this isn't it.

Characteristics shared by all members of the Unix family is that they are robust, stable, multi-user, and multi-tasking. Today, Unix is used for servers, desktops, laptops, routers, embedded systems, tablet computers, smart-phones and other mobile devices, such as digital cameras. When you know how to use the command line interface of any one of the members of the Unix family, you will also know most of what you need to use every other variant of Unix. There are difference between the family members, but they only surface for the more specialized tasks, such as system administration and system development.

Family members

Several different branches of the Unix family of operating system exist. The most popular variants are Gnu/Linux, FreeBSD and System V.

Gnu/Linux and FreeBSD are free software. This means that the software can be used, studied, distributed and modified without restrictions. The variants based upon System V are usually closed source software. This means that use requires a license from the copyright holder that imposes some restrictions on the user.

For each major variant there exists sub-branches. For example, Debian and Fedora are both based on Gnu/Linux, MacOS and Darwin are based upon FreeBSD, AIX and HP-UX are based upon System V.

Within the Gnu/Linux there are two major branches that most distributions are based upon. These are:

- Debian: Base for Ubuntu.

- Fedora: Base for CentOS and RHEL7.

On distributions based upon Gnu/Linux, the following command will print all release information:

$ lsb_release -a

You may also try these commands:

$ cat /etc/redhat-release # Red hat $ cat /etc/os-release # Ubuntu

Users in Unix

Unix is a multi-user operating system. Traditionally, it was used mainly used to run departmental computers with dozens, and sometimes hundreds, of different users.

With multiple users comes the need to distinguish one user from another, and to make sure they do not interfere with each other's work. This means that in Unix, users are identified by a specific user name, and they need to authenticate themselves to the system as part of logging in. There are also certain rules about what a user is allowed to do.

In addition to ordinary users, there is a superuser that traditionally have the user name “root” (but there is no rule that says the superuser must be named “root”).

The root user can do many things an ordinary user cannot, such as killing any process, and manipulate any file, including changing file ownership. The root user is also the only user allowed to bind to a network port numbered below 1024.

In this day and age, Unix is also used on single user laptop machines, owned and used by people who know very little about Unix. The rule, when a Unix machine is set up, is that the first user that is created becomes the all-powerful superuser. Some individuals that set up Unix on single user machines continue to use this account as their normal user account.

It is never a good idea to use the superuser account as a normal user account. Even super-experienced system administrators don't do this. The root account is really powerful, and Unix is not forgiving. Even a simple mistake, such as typing:

# rm -rf foo *

instead of:

# rm -rf foo*

may wipe your entire system.

Also, running malware as root will totally compromise the system.

So if you've set up Unix (i.e. some variant of Gnu/Linux) on your own computer, make sure you create a normal user account and use it for your day to day work. Then learn how to use the the sudo utility to switch to temporarily become the superuser, and only use it when necessary.

In this ebook, it is assumed that you're using Unix as an ordinary user, not as root or the superuser. If you want to learn how to use Unix as root, check out a book about Unix system administration.

Operating system components

When referring to an “operating system” in this ebook, I mean a kernel, a shell and a fairly standard suite of programs.

The kernel

The kernel performs all sort of important low level tasks of the operatings system, such as allocating resources (e.g. CPU time and memory) to programs, manages the file system, and handles communications in response to system calls.

The Unix kernel will not be discussed much in this ebook (to learn about the kernel, you need to pick up a Unix book with the word “advanced” in its title). But even beginners should know about the kernel and roughly how it fits into the big scheme.

The shell

The shell is the interface between the user and the kernel. When a user logs in, the log-in program checks the user-name and password, and then starts another program called the shell. The shell is a so-called command-line interface (CLI). It interpretes the commands the user types on the command line, and arranges for them to be executed (carried out).

The shell may execute the command it itself (in the case of a command that is built into the shell), or call upon the kernel and/or some other program to do so.

Interacting with the shell is the main topic of this book.

Standard programs

There are some basic programs you'll be sure to find on every member of the Unix family, such as programs to list, copy, rename and delete files, show help, or manage processes.

In this ebook I shall explain how to use the most useful of these standard programs. But don't expect to be told about every standard program that is part of the Unix environment. This ebook is just to get you started. When you've finished, you will have learnt how to use Unix to learn about commands and other parts of the Unix environment.

Processes and files

Everything in Unix is either a process or a file.

When a program is started on a Unix system, it becomes known as a “process” on the system. Every process is assigned a unique number called its “process id” (PID), and it can be manipulated by the user that owns it (and the administrator) by referring to its PID. We'll get back to processes later, but for know, you just need to know that a process with its associated PID is one of the basic concepts of Unix.

A file is a collection of data. They are created by users using editors, word processors, compilers etc., or imported to the system from the network or some recording device.

Examples of files:

- The source code of a program written in some high-level programming language. This is always human readable (plain) text.

- A document (report, essay, etc.). This may be plain text, or in some word-processor format that needs to be loaded into a word-processor to be read by humans.

- A media file such as a digital image, a video, or a MP3 music files. Media files uses formats that need to be processed by some media player to make sense to humans.

- A sequence of instructions that can be interpreted directly by the computer, but incomprehensible to an ordinary user. This is also known as an executable or binary file.

- A directory, containing information about its contents, which may be a mixture of other directories (sub-directories) and ordinary files.

In

Unix, directories are also files, and can be manipulated with the same

tools and commands as is used to manipulate other files.

In

Unix, directories are also files, and can be manipulated with the same

tools and commands as is used to manipulate other files.

The Unix file system

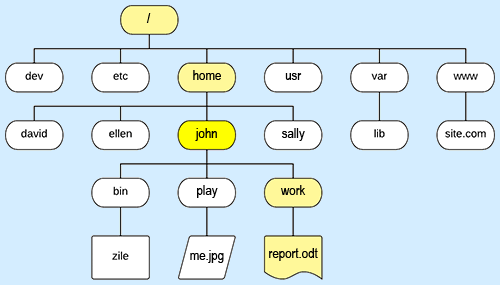

The Unix file-system is arranged in a hierarchical structure, like an inverted tree. The top of the hierarchy is called root (written as a slash – /).

A special place in the file system is your home directory. If your Unix user-name is “john” your home directory will also be named john. On most Unix systems, your home directory will be sub-directory of a directory named home, but other arrangements exists.

The illustration above shows (parts of) a typical Unix file system. The home directory of user “john” is marked with bright yellow.

Files in the Unix files system is uniquely identified by their absolute path from the root (/). The absolute path of the file report.odt /home/john/work/report.odt. This absolute path is shown in yellow.

The terminal emulator

To access the web server using the command-line interface (CLI) you use a terminal. It may be a physical terminal directly connected to a computer running some variant of Unix, but these days, it is much more usual to use a terminal emulator.

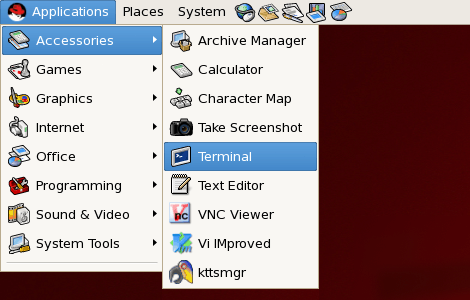

If your personal computer is running a version of Unix (e.g. Gnu/Linux or MacOS) a terminal emulator is already installed. If you're on a system without a GUI, the terminal is probably the only “window” on the screen. If your system has a GUI such as Gnome installed, the Terminal is found under .

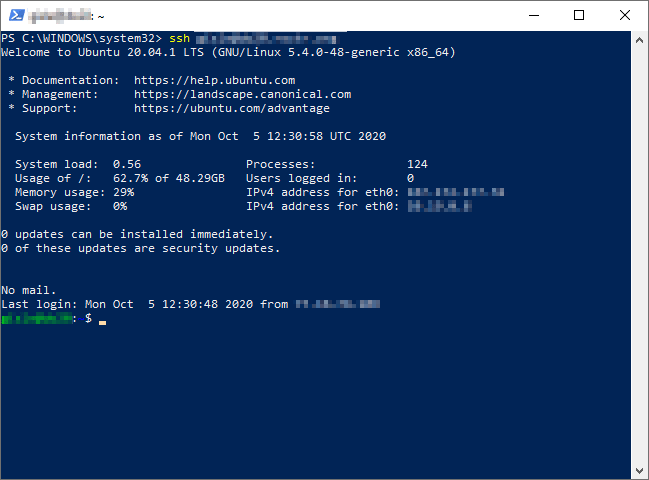

Some terminal emulators come with the operating system, and work work without configuration. The screenshot below shows the MS Windows 10 PowerShell: being used as a terminal to log in on a web server by means of ssh, a program that also is included in MS Windows 10:

For remote access to the web server's CLI from MS Windows, use the built-in PowerShell, Starnet's X-Win32 (commercial) or Simon Tatham's PuTTY (free software). For configuration and use of a terminal emulator on Microsoft Windows 10, see the Microsoft notes.

Provided your personal computer has a program named ssh installed. you can go ahead a connect to the web server with the following CLI-command (replace “username” with your own username on the web server and “example.net” with the name of the web server).

$ ssh username@example.net

The first time you connect to an unknown remote host, you may get a rather intimidating message and you will be asked if you want to continue connecting.

$ ssh username@example.net The authenticity of host example.net (xxx.xxx.xxx.xxx) can't be established. RSA key fingerprint is 53:b4:ad:c8:51:17:99:4b:c9:08:ac:c1:b6:05:71:9b. Are you sure you want to continue connecting (yes/no)? yes Warning: Permanently added example.net (RSA) to the list of known hosts.

Getting the message above the first time you use ssh to access a remote host is normal, and is no cause for alarm.

The first time you connect to an unknown remote host, you'll get this rather intimidating text and you will be asked if you're sure about connecting. You get this question because ssh provides host validation. To put it simply, ssh will check to make sure that you are connecting to the host that you think you are connecting to. If someone later poisons your DNS cache to trick you into logging into their machine instead so that they can sniff your session, you will be warned that RSA key fingerprint has changed.

Getting the message above the first time you use ssh to access a remote host is normal, and is no cause for alarm.

If you respond “yes” to this question, ssh will connect to the remote system and you'll be prompted to type in your password on the remote host. Since the session is encrypted, it is safe to type the password. If the password is accepted, you will be logged in on the remote host and get the standard login message (frequently a reminder of your last login. You then will get default prompt of the remote system – in this example represented with a dollar sign.

Names for commands and files

Notice that Unix is case-sensitive. Typing “RM” is not the same as typing ”rm”. All standard commands are written with all lower case letters. The same applies to file-names, so “myfile.txt”, “MyFile.txt”, and “MYFILE.TXT” are three different files.

Beware

if copying files from Unix to a Microsoft Windows machine. Microsoft

Windows does not make this distinction, so by copying files to

Microsoft Windows, you may end up overwriting files you did not intend

to overwrite.

Beware

if copying files from Unix to a Microsoft Windows machine. Microsoft

Windows does not make this distinction, so by copying files to

Microsoft Windows, you may end up overwriting files you did not intend

to overwrite.

Conventions

In this ebook, I shall use the following conventions:

- Names of websites, products, programming languages, standards and similar, are presented in an italic typeface (e.g.: Drupal.org, MS Office 2007).

- Command chains to navigate through menus are in a sans-serif typeface with a right arrow between the elements (e.g.: ).

- Words that you see on the screen, in menus and dialogue boxes are also presented in a sans-serif typeface (e.g.: Click to navigate to the next item).

- Names of files and directories are presented in a mono-spaced (typewriter) typeface (e.g.: unixpast.txt).

- Commands to be typed into the computer as they stand are shown in a bold mono-spaced typeface (e.g.

ls -al). - To indicate a a non-specific command, file or directory, a bold italic mono-spaced typeface is used (e.g.:

ls directory). You are supposed to substitute the italicised word with a suitable specific command name, file name or directory name. - A mono-spaced typeface is used for sequences of keystrokes (e.g.:

Ctrl+Shift+V), markup and code fragments, and CLI commands. - Words inserted within square brackets (e.g.

[Delete]) indicate a single non-character key to be pressed. - The

[Space]key is the large unmarked key at the bottom of the keyboard that inserts a blank space in text. - The

[Enter]key is never show as part of the command. But always, when typing in a command, you must press the[Enter]key. Commands are not processed by the computer until this is done. - The Unix prompt ($) is shown when appropriate. You should not type this in as part of the command.

- Ellipsis (…) is used instead of actual output when a command produces output it is not practical to list.

Example:

$ ls directory

This means: At the Unix prompt “$”, type “ls” followed by a space followed by the name of some directory.

Then press the [Enter] key.

In this case, you must pick the name of the directory.

Usually, examples of interaction with the shell, as well as sample scripts are separated from the running text in a box. This is how a short shell script will appear:

#!/bin/sh echo "Hi, $USER!" echo "The date and time now are: " date # EOF

Final word

[TBA]